It is the question of proximity, of where the writer stands as you turn the pages of her book. She stands behind you, her shadow cast. She stands before you, so that when you look up from the language on your lap, the only thing you see is her. She stands in the kitchen with a cup of orange jasmine tea while you—sprawled across the couch in the room beyond, one hand holding the book, one hand scratching the head of a fluffy cat—know only that she’s mysteriously near.

J. Williams Burns and S.D. Jones Williams are steeping their tea as you read their Edith Wharton’s Notebook, Donnée Book, 1900 [forthcoming, Tursulowe Press]. They are explaining, at the start, just what this volume is: “a chance to get closer to understanding [Wharton’s] creative process” by transcribing the notebook that Wharton kept during her 38th year, which is to say a year before Wharton bought the 113 Berkshire acres upon which she would build her Mount, five years before The House of Mirth, two decades before The Age of Innocence, two decades plus one year before she won the Pulitzer after Sinclair Lewis refused to accept it, and some time (choose the year) before Wharton would be canonized as one of America’s greatest writers.

The words Burns and Williams have painstakingly transcribed are the words of a writer finding herself, impressing herself, frustrating herself, reminding herself to buy malt (three glasses). They are the words of a writer trying out phrases and cutting their fat, replacing “exhaustive” with “encyclopedic” and “golden” hair with “hair glittered like the gold threads in an Easter chasuble.”

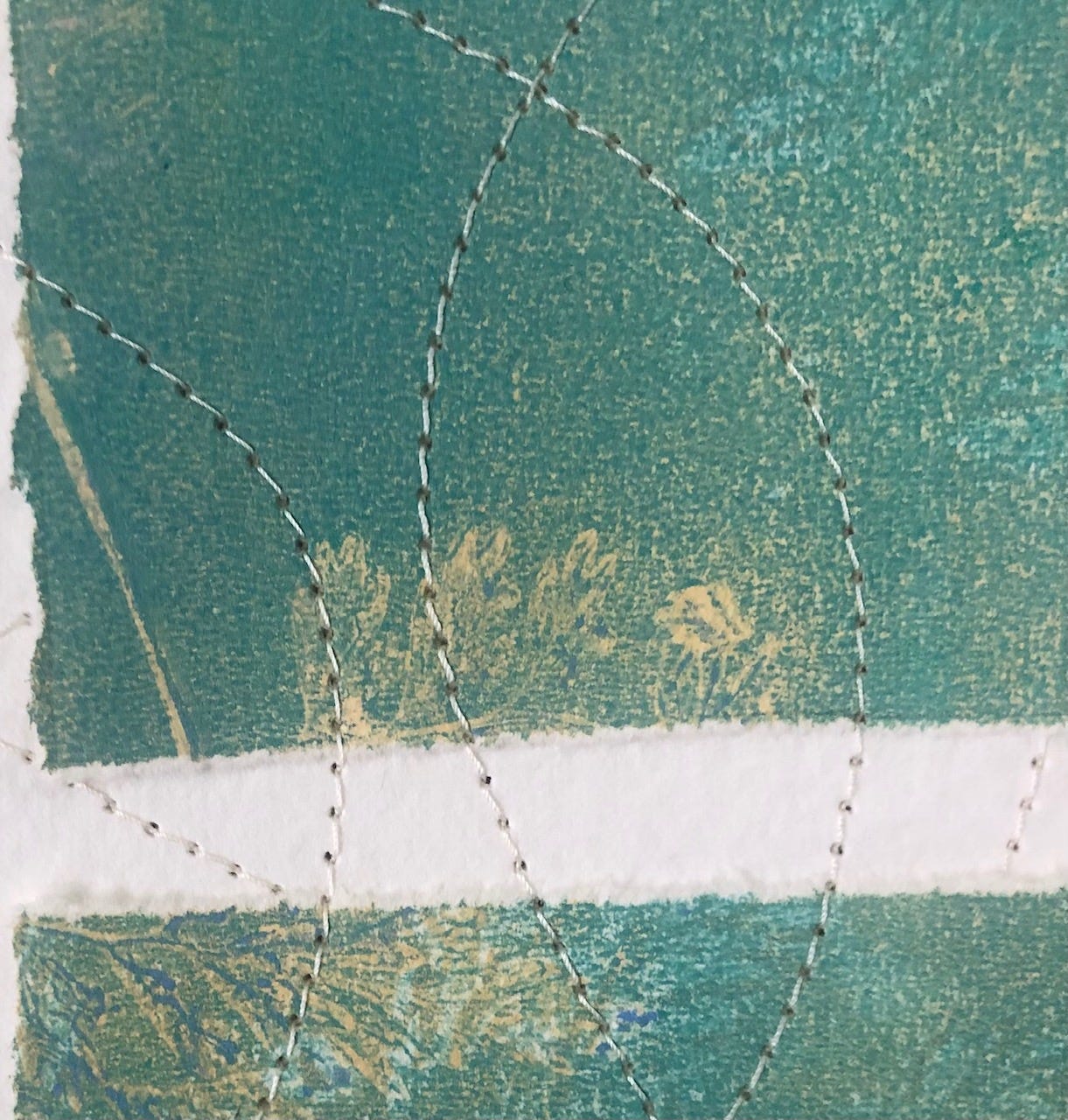

Wharton in her own ink on the verso. Transcription on the recto.

“Because these notes are handwritten rather than typed, they carry a certain emotional power and immediacy,” the transcribers write. “Many lines are crossed out—some with only a casual line-through, others with the vigorous and forceful back-and-forthing of her pen…. It is in this way that we can come away from certain sections knowing how she felt about her work as it was being written. There is something about watching her create, obliterate, and then recreate that comes close to being with her, as she writes, or at least as close as one can currently get.”

And yes, Burns and Williams tell us, some of the lines in this notebook will become lines in Wharton’s later stories, but the wonder of such detective work is a wonder the transcribers, now warming their tea, choose to yield to the you on the couch: “You will recognize glimpses of stories that are listed under their earlier names,” they write, “and you might spot some trenchant one-liners that are underlined in dog-eared copies of your own.”

The thrill, they say, is yours.

* I quote from Number 7 of 50, French-fold edition. I quote because this book was a pre-publication gift from my dear friend, Jessie Burns.

Beautiful, as I knew it would be. Welcome to Substack, Beth.

How wonderful to read this with early coffee! Glad you're here, Beth.