Note: I send this Substack deeply saddened by the terrible fires and destruction and grief of Southern California, the immeasurable losses. I want the winds to stop, the burning to end, the rebuilding to begin. I want, in other words, what we all want, and I want it, like I’m sure you do, so very desperately.

The post that follows takes a deep dive into the structuring of essays, memoirs, and stories, a topic that has arisen lately with a few of my beloved clients. The topic is broad. A single post can’t cover it sufficiently. I will revisit this theme in future Hushes and Howls.

***

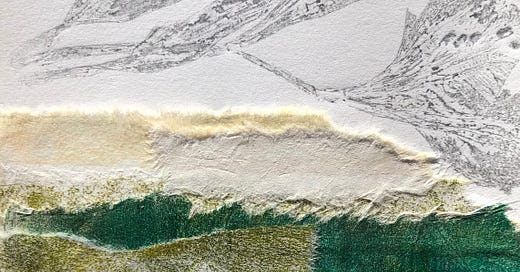

Maybe you, like me, begin with an image, a color, or a sound. A pulse of a thing. A dazzle. You need it, or it needs you, and so you write it down.

A sentence, now a paragraph. A grouping of passages. The beating heart of the story you wish to tell. An unfurling, an unfolding, a pen (or a keyboard) electrified with purpose.

At one point (after the first draft? after the second?), you will have some decisions to make about the structure of the thing that you are writing. Collage? Braid? Hermit crab? Wave? Spiral? Continuum with chapter breaks? An epistolary exercise? A story collection or a book of essays or a memoir-in-essays or fragments, like pebbles, arranged within the expansive white space of each page?

Will you think, as Abigail Thomas often thinks, of your work as a story contained within three parts? Will you, like Heather Christle in The Crying Book, arrange your splinters according to metaphor? Will you, as I attempted in My Life in Paper: Adventures in Ephemera, create a pattern that moves across universal inquiry, the personal, and the historical in a way that requires much thought about typefaces? Will you, as I did in my new novel, Tomorrow Will Bring Sunday’s News, fly your arrow of time backward, and forward, but also in circles?

Structure is what tells us what our story is. It is our culling system (what fits? what doesn’t?). It is, as my friend Cynthia Reeves says, meaning itself, not to mention one essential means of suspense and surprise. Structure is what teaches us whether our embedded flashbacks or flash forwards are too verbose, whether our tangents are a tad indulgent, whether our narrative is too thin, whether we have, as writers, taken a journey and learned something new about ourselves, our literary ambitions, and our capacities as puzzlers. Structure is a container, of sorts, a container that teaches our readers how to read our books, and also, perhaps, how to read us.

Consider the container of Margaret Renkl’s gorgeous first book, Late Migrations, a compilation of small essays about the natural world and personal grief. The stories of backyard birds, snakes, dirt roads, and bees sit companionably beside stories of the author’s own childhood, young adulthood, and fully adult grief. The book is structurally bound—contained—by thematic adjacencies. A short piece called “Nests”—about backyard birds and a snake—precedes a piece called “In the Storm, Safe from the Storm,” which is all of two gorgeous paragraphs about young Margaret sitting with her father in a doorway jamb, watching the rain and feeling safely nested.

Later, a piece called “Things I Knew When I Was Six” is answered, on the next page, by “Things I Didn’t Know When I Was Six.” The structural patterning—the metaphorical natural world and Renkl’s lived life of loss (and beauty)—is quiet, never forced, but absolutely there. You sense the authorial intent. You feel the rhythm’s beat and rise. You reach the crescendo. You exhale. The book ends. The stories Renkl chooses to tell about her backyard world make room for her life stories, and vice versa. Each type of story is finely tuned, one to another. A unified whole. A book that wants no more or less.